Writing haiku appears easy, yet it involves more than counting syllables. To truly grasp this ancient art and give it a shot yourself, explore its profound history and beginnings further.

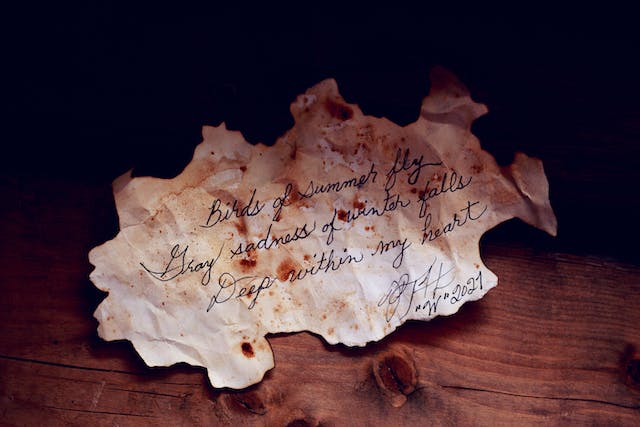

Haiku, a form of poetry originating in Japan, typically comprises three lines with a syllable pattern of 5-7-5. However, it’s not merely about syllable count; it captures fleeting moments in nature or life, often revealing deep emotions or insights within a concise structure.

This poetic form traces back to the 17th century, developed by poets like Matsuo Basho, who emphasized simplicity and a connection with nature. Haiku seeks to evoke emotions, painting vivid scenes in few words, and employing seasonal references called “kigo.”

Moreover, writing a haiku involves observing the world keenly, focusing on small details, and often juxtaposing contrasting elements. It encourages contemplation and the appreciation of life’s fleeting moments.

What is a Haiku Poem?

A Haiku is a type of poetry that originated in Japan. It uses short lines without rhymes and paints pictures of nature. Imagine capturing a moment in nature, like a bird in flight or a blooming flower, using only a few words.

Typically, a Haiku follows a structure of three lines. The first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and the third line has five syllables again. This structure helps to create a rhythm and a sense of balance in the poem.

Haikus often focus on seasons, sensations, or fleeting moments. They aim to capture the essence of a single scene or feeling, making readers pause and reflect. Some traditional Haikus also include a word or phrase called a “kigo,” which indicates the season or time of year.

Japanese poets have used Haikus for centuries to express their observations and feelings about the natural world. Today, people worldwide write Haikus as a way to connect with nature and express moments of beauty or insight in a concise and vivid manner.

History of Haiku Poem

Haiku is a poetic form traced back to ancient Japan, and evolved through various stages before becoming the concise and expressive art we know today.

Initially, it emerged from the intricate structure of renga, a collaborative poem exchanged among poets. Renga involved strict rules and a specific format, commencing with a short verse known as hokku. This precursor to haiku sets the seasonal tone within three phrases of five, seven, and five sounds.

In the 16th century, poets separated hokku from renga, leading to the development of a more relaxed and humorous form called haikai, notably refined by Matsuo Bashō in the Edo Period. Subsequent poets like Yosa Buson and Kobayashi Issa continued this evolution, finding humour in everyday subjects.

The Meiji Period saw further popularization by poets like Masaoka Shiki, marking the transformation of hokku into an independent poetic form called haiku.

Haiku’s influence gradually extended beyond Japan. In the 19th century, it journeyed to Europe and North America. Renowned figures like Ezra Pound adapted its essence into their works, even if not strictly adhere to its traditional structure. Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” exemplifies this, juxtaposing vivid images of haiku’s spirit.

In the 1950s, Beat poets drew inspiration from Eastern philosophies, notably influenced by R. H. Blyth’s translated Japanese haiku in his work “Haiku,” which introduced English-speaking readers to this captivating art form.

Also Read: What Is a Rhyme Scheme? 8 Examples in Poetry

What is the Traditional Structure of Haiku Poetry?

Haiku poems have a traditional structure that can be a bit tricky to define when moving between languages. When translating haiku, the syllable count and sentence structure often pose challenges. Some translators suggest that twelve syllables in English might better match the seventeen morae (sounds) known as “on” in Japanese haiku. This helps maintain a similar rhythm and essence.

Moreover, the way haiku is presented differs between Japanese and English. In Japanese, haiku typically appears in a single line, but English poets break their haiku into three lines with two-line breaks. This difference in formatting doesn’t change the essence of the poem but showcases how language nuances can affect its appearance.

Furthermore, the essence of haiku extends beyond structure; it embraces capturing a fleeting moment or nature’s essence. It’s about painting a vivid picture with a few carefully chosen words, inviting the reader to experience a moment’s beauty or depth. Despite these structural disparities in translation, the core spirit of haiku remains consistent across cultures.

The Key Rules of Writing a Haiku Poem

Haiku poems usually have three lines and follow a specific structure. This structure involves using a total of seventeen syllables, divided into three lines: five syllables in the first and third lines, and seven syllables in the second line.

Haikus are a form of poetry originating from Japan, focusing on capturing a moment or feeling in a concise manner. They often emphasize nature and evoke vivid imagery within the limited syllable count.

Adhering to these rules helps maintain the essence and beauty of a haiku. They encourage writers to be concise yet descriptive, capturing the essence of a moment in a precise and evocative manner.

The simplicity of these rules allows writers to explore creativity within a confined structure. Despite their brevity, haikus have the power to convey profound emotions and imagery, making them a cherished form of expression in the world of poetry.

Key Features and Traditional Elements of Haiku Poetry

Haiku poetry centres around nature and the seasons, often capturing vivid imagery in a concise manner. Beyond the customary focus on seasonal themes, there are specific elements to note when diving into haiku writing:

- Kigo – Seasonal Words: Traditional haiku incorporates a ‘kigo,’ a word or phrase that signifies a particular season. For instance, ‘sakura’ (cherry blossoms) represents spring, ‘fuji’ (wisteria) symbolizes summer, ‘tsuki’ (moon) embodies fall, and ‘samushi’ (cold) signifies winter. These words economically evoke a seasonal essence, enhancing the poem’s depth.

- Kireji – The Cutting Word: Known as the “cutting word,” ‘kireji’ introduces a pause or break in the poem’s flow, often juxtaposing two distinct images. While contemporary haiku may vary in their use of ‘kireji,’ the technique of contrasting elements remains a prevalent characteristic.

- Nature and Seasonal Depictions: Haiku originated as a medium to depict seasons, and modern poets continue this tradition by emphasizing the natural world and its seasonal transformations.

- On – Sound Units: Japanese haiku consists of seventeen ‘on,’ or sound units, differing from English syllables. Translating haiku into English presents challenges as the syllable count doesn’t precisely mirror the original ‘on’ count, leading to debate among translators about capturing the true essence of haiku in English form.

Also Read: 85 Similes Examples

Examples of Haiku Poem

Haiku poetry captures moments in a few short lines. Matsuo Bashō, a renowned master of haiku, crafted verses that beautifully encapsulated nature and human experiences. Here are some examples of his celebrated haikus:

1. An old pond!

A frog jumps in –

The sound of water.

This haiku paints a serene picture of nature, focusing on a tranquil pond disrupted by a frog’s leap, creating ripples and a subtle auditory delight—the splash of water.

2. A caterpillar,

this deep in fall –

still not a butterfly.

Bashō reflects on the transformation of a caterpillar, emphasizing the continuity of life even as the seasons change, conveying patience and the beauty of natural progression.

3. In Kyoto,

hearing the cuckoo,

I long for Kyoto.

This verse expresses a deep longing for a familiar place, as even the sound of a bird in a different location evokes nostalgia and a yearning for home.

4. Taking a nap,

feet planted

against a cool wall.

Bashō captures a simple moment of relaxation, where the sensation of coolness against the feet while napping becomes the focal point, inviting readers to feel comfort and peace.

5. When the winter chrysanthemums go,

there’s nothing to write about

but radishes.

Here, Bashō portrays the transition of seasons and the inevitable absence of inspiration, highlighting the mundane aspects of life—a thought-provoking observation.

6. Teeth sensitive to the sand

in salad greens —

I’m getting old.

This haiku touches on the inevitability of ageing, using a sensory experience to convey the changes that come with growing older.

Matsuo Bashō’s haikus often conclude with lines that provoke contemplation, inviting readers to reflect on the subtle beauty of everyday experiences. His mastery lies in capturing fleeting moments and emotions within the constraints of a few carefully chosen words, painting vivid images in the minds of those who read his poetry.

Haiku, as demonstrated by Bashō, invites us to appreciate the simplicity of life, finding beauty in the ordinary and fleeting moments that often go unnoticed. Through these poems, one can embark on a journey of introspection and connection with nature, discovering profound meanings in the seemingly mundane aspects of existence.

A Step-by-Step Guide on How to Write a Haiku Poem in 4 Easy Steps

Writing a haiku poem can be simple and rewarding. Here’s an easy-to-follow guide to help you craft a perfect haiku in just four steps.

- Choose Your Haiku Style: Decide what type of haiku you want to create. Traditional haikus follow a structure of five-seven-five syllables across three lines. However, you can also experiment with different syllable counts or structures. If you find your haiku could be expanded, consider using it as the beginning of a tanka poem or explore haibun, a blend of haiku and prose.

Expanding on Styles: Haiku offers flexibility; you can play with syllable counts or formats, allowing for more creative expression. Tanka poems extend the haiku, adding two more lines of seven syllables each, deepening the poetic narrative. Haibun, on the other hand, combines haiku with prose to create a rich, narrative form.

- Find Your Subject: Look closely at your surroundings and focus on the little things. Haikus often centre around nature, so observe the details of the world around you. Notice birds chirping, leaves rustling, the scent of flowers, or the sensation of the air. These simple, everyday elements make excellent subjects for haiku.

Exploring Nature’s Beauty: Nature provides a vast canvas for inspiration. Delve into the beauty of the natural world, capturing moments that often go unnoticed. Each season offers unique imagery—like the vibrant colours of autumn leaves or the budding blossoms of spring—perfect for evoking emotions in your haiku.

- Craft Vivid Images: Use concise phrases that paint vivid mental pictures. Emulate the Japanese concept of ‘kigo’ by selecting images that represent a specific season. For instance, fallen leaves signify autumn, while daffodils symbolize spring. Through carefully chosen words, create a mood or emotion within your haiku.

Visualizing with Words: Haiku thrives on simplicity. Engage your reader’s senses by using descriptive language that captures fleeting moments. Harness the power of imagery to transport your audience to the scene you’re painting with words.

- Employ the ‘Cutting Word’: Introduce a ‘kireji’ or “cutting word” to punctuate your haiku and create a pause or break in the rhythm. Use punctuation strategically in conjunction with the ‘kireji’ to control the flow and pacing of your poem.

Mastering Rhythm and Pause: The ‘kireji’ acts as a pivot, infusing depth into your haiku by altering its rhythm. Experiment with punctuation—like dashes or ellipses—to create pauses that heighten the impact of your words.